by KJ Hellis and Brian Amdur

In 2016, photographers KJ Hellis, Brian Amdur and Kazumi Eckenstein traveled with professor Marquis Blaine to the barrier islands in Cordova, Alaska. What they discovered on Hinchinbrook Island were miles of beaches strewn with plastic from around the world. A toothbrush from Korea, a juice bottle from China, the sole of a shoe from Spain. It became apparent that the plastic that now contaminates beaches in Alaska, did not originate from the state, or even the country they were found in. What ensued was an investigation and a closer look at where this plastic came from, it's journey through ocean, and the implications it has on taking over local environments.

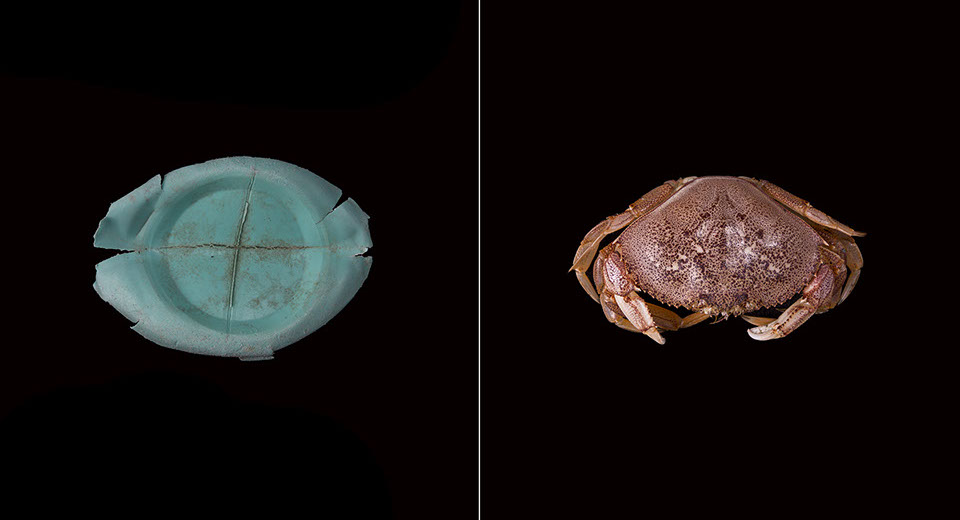

A neon green dish soap bottle is manufactured by the company Lix. Lix is a Vietnamese brand which manufactures cleaning products including dish soap, toilet cleaner, and detergent. A long piece of driftwood has been sanded smooth by the tides. In native Eyak culture in Alaska, driftwood is used to build huts and boats.

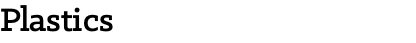

A small piece of blue cord is broken off from the larger net. These ghost nets can entangle and trap any marine animal including sharks, turtles, and dolphins. The sharp material of the nets can lacerate the bodies of marine animals and can drown others that need to surface for air. A sprig of common horsetail, or Equisetum Arvense, was found on the beaches of Hinchinbrook Island.

On a remote island accessible only by boat or bush plane, what first meets the eye is exactly what you might imagine: untamed beauty, glistening sand so caked with intricate shells and empty elaborate mollusks that it makes you question the value of the sparkles we so often desire. In a matter of a few hundred yards, the beach transforms into a forest filled with dignified green giants. This is Hinchinbrook Island.

Located in the Gulf of Alaska at the entrance of Prince William Sound, the island played host to only five permanent residents as of 2000. Yet with so few inhabitants, traces of human life are oddly ubiquitous. Trash—waste, litter, junk, debris, and garbage—so sand worn and tired that it almost blends in with the bleached driftwood that also loiters on the island’s shore. The waste has made Hinchinbrook’s beach its retirement home, forced there by the same hands that once held it. A beach you’ve never heard of. A beach that you would unlikely be able to access yourself. A beach so full of natural beauty, that to lay your eyes upon its beige-crusted shoreline might make you envious of something unexpected—your trash.

On the morning of June 16th, I woke up in Cordova, Alaska, nestled deep within blankets on a twin bed at the Orca Lodge. It was early but bright—then again, it was always bright. More than 19 hours of sunlight are present daily during the month of June in Alaska. Cordova is one of the best places in the world to study the detrimental effects of climate change on a natural environment. The University of Oregon has made a habit of doing just that, through the School of Journalism and Communication’s Science and Memory project. Returning each summer and piloted in 2013, our cohort of 12 was the third group to take part in Science and Memory. And four of us were about to go somewhere that no one in our program had been before.

After stumbling out of the coziness of our beds and slamming down some coffee, our small group (including University of Oregon students Brian Amdur, KJ Hellis, and myself; and Professor Mark Blaine) hopped into a rented silver SUV and blundered down a dirt road toward Merle K. “Mudhole” Smith Airport. There, we met the incomparable Steve Ranney, Alaska Extraordinaire and our pilot for the day. Ranney is the son of one of the first female Alaskan bush pilots, has knowledge of each mountain, stream, and (probably) pebble in the area, and is someone who has supported the Science and Memory project since its inception.

As we all gathered in his homey office pre-flight, Ranney went over the basic safety protocols of flying in his Cessna-185. Happily nodding along as he discussed earmuffs, seat belts, and windows, the nodding promptly stopped after Ranney uttered two words: weight load. We all knew what was coming next. “How much do you weigh?” he asked the four of us. Calculating our answers, we looked around at one another, knowing our lives depended on the truth. The same thought rang throughout each of our heads: How much do I actually weigh? There was no room for rounding down.

Ranney’s weathered hands pointed to a map depicting the Gulf of Alaska—Hinchinbrook Island so minute that this gesture completely concealed it under his right index finger. The purpose of our journey that day was to view, up close and personal, a destination of global waste accumulation. But how could this tiny island be that destination? None of us were aware of it yet, but the irony of Hinchinbrook Island was beginning to present itself on a silver platter. You may never have access to this picturesque island, but your garbage might—its mode of travel: ocean currents.

The world’s oceans are constantly in fluctuation with one another. All work together in a cyclic nature to push and pull seawater to distant lands. These currents play a large role in determining which innocent islands, such as Hinchinbrook, will be dumping grounds for waste from across the world.

In a systems analysis project conducted by the Presidio Graduate School in 2016, a group of students, discussed how discovering a piece of trash in the Pacific Ocean does not necessarily mean that it came from a Pacific coastline. The team outlined the National Drifter Program, saying, “Between 1977 and 1993, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration placed 2,000 drifters in oceans across the world to see their travels. The drifters are still present in the water today and show the extent to which objects can travel across the planet [via the ocean].”

A large system of currents, all part of the North Pacific Gyre, forces water and its contents up into the Gulf of Alaska. Not only does the North Pacific Current flow through this zone, but it is fueled by the Oyashio and Kuroshio Currents, which run along all of East Asia. This means that the seawater surrounding both North and South East Asian countries travels in the same direction, islands in its path acting as temporary loading docks for the water’s contents.

As we boarded Ranney’s Cessna 185 he directed us into seats, distributing our weight properly throughout the plane (thank God for our earlier honesty). I was shoved to the back in the kiddie-seat, a bit claustrophobic but the only one that had access to windows on either side. Brian and KJ sat next to one another in front of me, and Mark was upfront with Ranney. The weather was perfect, blue skies and no clouds. Once we were settled, Ranney started his plane, turned a corner, and within seconds we ascended into the sky off of a gravel takeoff strip. The Alaskan scenery that surrounded the plane in all directions made our time in the air feel much longer than the short 15-minute-flight we were taking.

To the left of the plane, the Copper River filled with murky glacial sediment flowing like veins throughout the land and into the bright blue ocean. To the right, an entirely different environment, created by the Great Alaska Earthquake of 1964. The 9.2 magnitude quake thrust certain areas up by as much as six feet, and a new ecosystem was born. Vibrantly green and swampy, we spotted a small herd of moose tramping through the colorful landscape below us.

Before making our final dip toward Hinchinbrook, we soared above the coastal waters of the Pacific. The lines of commercial fishermen below us having one of the worst sockeye salmon seasons in recent history. Sockeyes, or as locals call them, “reds,” were not emerging from the depths of the ocean as they normally did. It wasn’t that the reds had disappeared, or were suddenly aware of the fishermen lurking above—the seawater where the fishermen sat was simply inhospitable. In just one year, the water had risen by more than five degrees. That may not sound like much, but think about how you’d feel if your body temperature went up by five degrees—not great, right?

The tide determined our time of arrival, as Ranney used the damp sand as a landing and takeoff strip. We descended toward the island parallel to the ocean—a split second of uneasiness, then a collective sigh of relief as we glided safely to a stop on the shore. We hopped out of our ride and the heavy rubber boots adorning all eight of our feet sunk firmly into the sand. Ranney took off in the same direction from which we came, and our only transportation on and off the island, disappeared into the distance. It was 11:00 a.m. Ranney would be back for us around 4:00 p.m., when the tide was low again. There was no time to let the feeling of absolute isolation sink in—we only had five hours—in an area none of us had any prior knowledge of.

KJ and I started by taking an ordinary walk along the beach, attempting to count our steps as we went. “Ordinary” in that many people have taken a walk on a beach; however, not ordinary, was the walk itself. The loose sand and our heavy boots provided for awkward strides and heavy breathing. We hurriedly counted each step, attempting to get a frame of reference for the area we would be covering. It was comical—but letting out even a soft chuckle would mean losing track and having to start over. We remained focused—and sweaty—838…839…840…done. Initially, our plan was to count the total amount of waste in the area of beach between our 840-step walk and the forest, where the beach ended. After starting, however, we came to the conclusion that this task would be impossible to complete due to our time constraints.

Instead, we chose a smaller plot that could be generalized to most of the shoreline, an area about the size of a doubles tennis court (around 15 of these plots filled our original “beach walk”). The scientist inside of me screamed—for the past six years I’ve worked in laboratories where the difference of one millimeter is enough to cause invalidity. But this was different, and the other parts of myself (the explorer, the writer) fought back. This was about us, about you, about discovering beauty, about the human experience—none of which are defined by one thing.

Each piece of trash on that beach had been someone’s. It was touched, used, held, and discarded—maybe lost—by another person. And in the heat of that June day, the junk that once filled another’s life transformed into stories, into fascination, and into treasure.

A cracked yellow construction hat with a blue sticker displaying Asian characters on it stuck out of the sand. When was the last time it was worn? Was it from the 2011 Japanese tsunami, as much of the trash that washed up on Alaskan shores was? Was whoever last wore its fate decided by the ocean as well? These questions racked our minds, but only for an instant, until we discovered another piece that begged its own set of questions. We were kids hunting for buried treasure. We each hustled along the beach, trying to find the “best” piece of trash before someone else, and proudly shouting, “Look what I found!” while holding up a raggedy shoe, or a bottle containing unknown contents, or a weathered nylon net. It was weird. It was fun. It was trash.

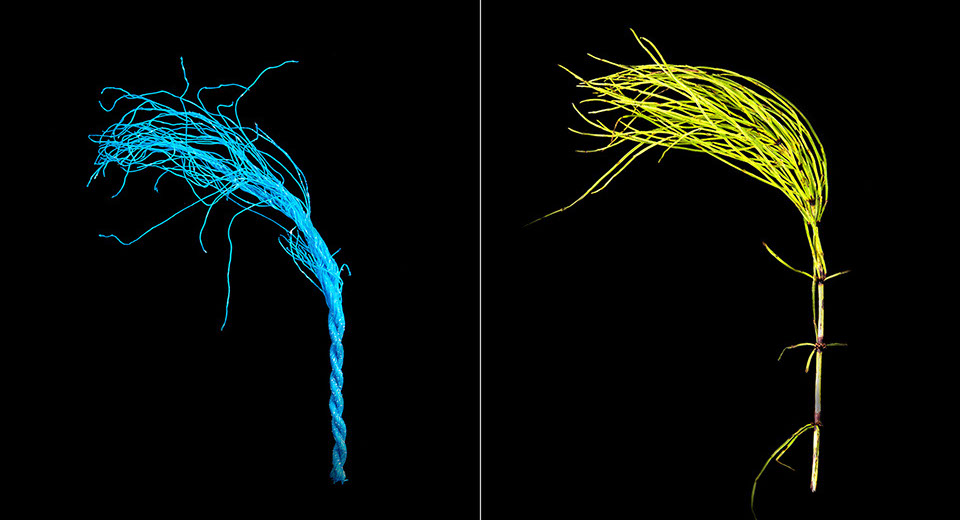

Each year, eight million tons of plastic enters the ocean from land (Jambeck, 2015). Only a tiny fraction of that eight million washed up on Hinchinbrook’s shore and into our plot. The 143 pieces we counted in this area ranged from bulky discarded matter to tiny indistinguishable shards. We found discernible items including a jade-colored bottle labeled “Lix”, a detergent company in Vietnam; a violet toothbrush with the words “Dr. Clio” on the handle, a toothbrush production company from Korea; and a hunk of burnt-orange plastic that read “Dallas, TX.” The amount of debris from seemingly distant Asian countries was shocking; but we would later learn that over 50 percent of ocean plastic originates from just five countries: China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, according to a 2015 study titled Stemming the Tide, released by the Ocean Conservancy and McKinsey Center Business and Environment.

We also found items that were completely indistinguishable, mostly broken up shards of multicolored plastic. Somewhere between the indistinguishable and the unmistakable, were most of our finds: empty plastic water bottles with no markings, the sole of a long forgotten shoe, and a yellow rubber ball with a smiley face on it (to name a few). Research shows that the amount of plastic entering the ocean is increasing rapidly year by year. If action is not taken, by 2025 the cumulative sum of marine plastic debris is predicted to reach 250 million mega tons (Jambeck, 2015). It’s hard to imagine naturally picturesque islands, such as Hinchinbrook, consumed by even more trash than they already are.

Around 2:00 p.m., after relentlessly digging through the sand for around three hours, we were all exhausted. Shade on the beach was non-existent. Brian, KJ, and I rested on a large piece of dried driftwood. No one said a word; preoccupied, in part, by the copious amount of water we were each gulping down, but more so because no one had the energy to chat. Gazing out toward the ocean in front of us, KJ broke the silence, “I’m going swimming,” she said as she hopped off the dried log. Brian and I followed.

The water was cold, but it was exactly what we needed. Packing for Alaska, I never thought about the possibility of going swimming. But there we were, relaxing in the waters of the Alaskan Pacific. As land-living animals, the interactions that most humans have with the ocean are brief, and often in search of benefits such as food or relaxation. We are lucky—for marine animals, life in the world’s oceans is becoming increasingly hazardous. A plethora of research shows that marine plastic debris is killing, injuring, and reducing the reproductive rates of marine mammals, seabirds, and fish. We might only notice the unsightly amount of plastic debris once it washes up on shore, but for marine animals, it’s a constant part of their lives. In 2002, José Derraik published a “review of most of the literature published thus far” on the topic of the effects of plastic debris on the marine environment. He concluded that of all marine mammal species, 26 have died as a result of plastic ingestion, and 43 percent have been negatively impacted. For these species, seawater is equivalent to the air we breathe. If something pollutes it, their whole world is in jeopardy.

The more widely recognized problems with marine plastic pollution are usually associated with entanglement, ingestion, suffocation, and general debilitation, according to a 2009 study conducted by Murray R. Gregory from University of Auckland in New Zealand. But there is another formidable issue—a silent killer: microplastics. When plastic items are improperly disposed of and end up in seawater, they breakdown into smaller and smaller pieces, and can eventually become microscopic. This makes it easy for microplastics to infiltrate the world’s oceans; they have become increasingly abundant. One study conducted by researchers at Dartmouth College in 2014 even found microplastics in Arctic sea ice. For marine animals, continuous consumption of microplastics is unavoidable. I don’t doubt that we consumed small amounts of microplastics during our short ten-minute swim—but we got to get out. The ocean had given us new energy. We slowly waded out, put our boots back on, and continued to search for the world’s best trash.

Around 3:00 p.m., one hour before Ranney would return, we congregated our loot from the day. There was only so much more weight that could be added to the plane, so we had to pick and choose which pieces we would want to bring home to take a closer look at. As we collectively decided which pieces to keep, an odd sense of attachment came over our group. The trash had become dear to us. The thought of leaving some of it behind, on an island we might never return to, was almost sad.

Out of water, we decided to look for the Forest Service cabin that Ranney had mentioned to us earlier, in hopes of finding some hydration. Mark noticed a small path winding through the back of the beach where tall grasses sprouted up from the sand and led to a dense forest. There it was, a triangular wooden cabin, its slanted roof stopping just above the ground. Surrounded by shade, the temperature was significantly cooler than on the beach. A stream of water trickled nearby, but there was no tap or fountain to be found—we would just have to wait. The cabin itself was open. In the deep wilderness of Alaska, cabins, such as this one, are often left unlocked, in case an unlucky traveler must seek shelter. It was a cozy space, complete with a small kitchen and sleeping pads. Directly out front of the cabin was the real fun.

Nylon nets suspended over the space between trees created two large makeshift—and comfortable—hammocks. An orange and white-striped buoy, attached to a rope, dangled from another nearby tree, creating a swing. KJ went for the swing, but after a few moments joined Mark, Brian, and I as we rested on the hammocks. It was an interesting change of scenery. Moments ago we were searching through unwanted nylon nets and castoff buoys that were lying uselessly on a beach—now, we were utilizing them. This all due to someone’s simple idea to take something that was discarded and make something of it.

A 2010 research project titled “Economic Impacts of Marine Litter” found that more than $24 million is spent annually cleaning plastic refuse from coastal areas. Further, according to a 2011 US EPA report, the primary source of marine debris is the improper waste disposal or management of trash and manufacturing products, including plastics. If more companies decided to reuse or recycle such manufacturing products in simple ways, the amount of marine debris would drastically decrease, and loads of money would be saved, as companies would be reusing material they already own.

As we waited for Ranney’s return, I thought about what a fun and beautiful day it had been—how odd considering we spent it collecting discarded plastic and trash. In the distance, we heard the familiar sound of a plane, and within five minutes, Ranney had landed on the beach.

This was goodbye. We had gotten to know this beach, we had rummaged through its most personal artifacts, discovered what lay beneath its outer beauty, and now we were leaving? Was it sadness I felt? Was it pride? Was it guilt? Who knows, but the one thing I am certain of is that I will never forget the beauty of Hinchinbrook Island—or that yellow construction hat.

by Kazumi Eckenstein