By: Tim Vandehey, Jeff Dean & Morgan Krakow

A fish ladder acts as a detour for fish to migrate around an impediment in the water such as a dam. The Winchester fish ladder has a series of shallow pools that ascend the height of the dam. The fish leap from pool to pool and rest in between jumps. This fish ladder has two entrances, low and high flow, for fish to use depending on the seasons and height of the river.

Each fish ladder has to be tailored to the type of fish that will be using it, some fish ladders can be steep and have a fast current whereas other types of ladders are less challenging to go up. Fish ladders are not 100% effective and can sometimes slow down migration upstream. The log deflector directs the flow of water down the dam.

Illustration by: Anna Rath

Salmon take a variety of paths to get past the Winchester Dam using the site’s fish ladder. Fabian Carr, Fish Technician with Oregon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), points out the channel that Spring chinook salmon use during their migration upstream. During the last 10 years, the amount of Spring chinook that pass through the fish ladder has dropped 29.5%. The various species of fish pass take different approaches to the ladder as the water level fluctuates throughout the year. During the warmer summer months, the salmon tend to lay low in shady areas as the stress of moving up the fish ladder can often be fatal.

The fish go through a series of 15 ladders to get above the dam. Though the dam is 16 feet high, it still takes a lot of work for the fish to climb up the ladder. The powerful salmon jump up the ladder one segment at a time with working their way upstream. Carr has watched an adult salmon swim up the ladder in 40 seconds.

Prior to the 1964 improvement of the fish ladder, fish counting was more challenging for the ODFW. Fish counters would work during daylight hours counting the fish that swam over a white board located below the counting station. ODFW uses the fish ladder to conduct research on what types of fish are migrating through the waters of the North Umpqua River.

ODFW uses the suspended bucket crane to collect brood for the hatcheries in the district. The crane is suspended on a series of high wires and it moves fish from the river to a liberation truck that takes the fish up the road to the hatchery.

The powerhouse on the North bank of the dam was built in 1983 as an effort to bring hydroelectric power back to the Winchester area. The fish counting station (located inside) was remodeled during the construction though the push for hydroelectric power was abandoned in 1985.

Two video cameras record on a time lapse setting 24-hours a day. The fish that pass through the ladder are recorded to a DVR located on site and analyzed remotely at the Roseburg Umpqua Watershed District Office. ODFW record specifics on each fish that is captured in the fish ladder.

Inside the fish counting office, Carr demonstrates how to open and close the viewing station for passage. ODFW closes off the counting station to water passage to clean the area that is recorded. Water debris piles up and in order to record the average 30,000 fish that pass through the fish ladder, the station needs to be cleaned on a routine basis.

In 1991 the state switched to video recording streamlining the fish counting process. Carr sits at the fish viewing station amongst a mass of cables and explains the process in which the footage is analyzed.

Three hats hang in Carr’s office: one for Hunting season, a warm winter hat, and a thick canvas hat for rainy days.

On the wall of his cubicle lies the “Wall of Catches” which includes historical images from around the area as well as former co-workers with trophy sized creatures.

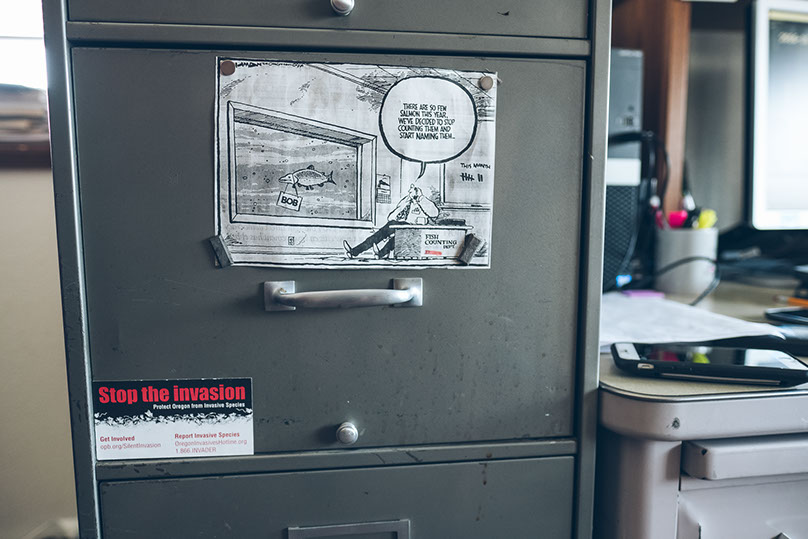

Amidst the chaos of the office, the filing cabinet provides comic relief on the harsh reality that can be his job. Fish Technicians help to set fishing regulations in their district in order to maintain fish populations around the district.

Carr spends few hours at his desk, most of his time is spent in the field traveling to different sites to conduct research and data. He knows every shortcut and fishing hole in Douglas County thanks to his 22 years of working for ODFW.

<

>